Back in 2012, BMWBLOG had the opportunity to interview Chris Bangle, BMW’s ex-chief designer.

There are a number of us at BMWBLOG that think very highly of Chris Bangle’s contribution to automotive design and particularly to his contributions to BMW. To highlight that regard, here is a quote from an article published on BMWBLOG that summarized what we thought Bangle’s legacy to BMW was, “(w)hat Bangle has done at BMW, more than any pen to paper exercise, is to build a design staff that embraces passion and beauty which then clothes the driving dynamics of BMW. That is the legacy of Chris Bangle.”

So at the time, rather than focusing on BMW, we wanted to hear from Bangle what his vision for future design is and how the automotive landscape is changing. Nearly three years ago, Bangle talked about electric cars, self-driving automobiles, user interfaces and much more.

BMWBLOG (BB): What do we need to look at, what things should a casual observer be looking at in order to understand what influences design – how can they look at the world differently? How does a designer look at the world?

Chris Bangle (CB): That’s a really good question.

Well, not all designers see the world the same. Let’s stay in the world of the car designers. Some car designers see the world as just fine; it just isn’t quite tuned the way they would do it. So their “shtick” is to do what everyone else has pretty much done, except do with their own footprint. As a consequence their work looks pretty much like everybody else’s, except slightly different.

There are other people who see the world as something that is absolutely foreign to their concept of how things should function. These designers are pretty intolerant and tend to create things which have almost nothing to do with anything else, primarily because they don’t give a damn about it. That doesn’t necessarily make their work usable; quite often these people are super fanatic about what they do and they just can’t understand why everybody else doesn’t see it that way.

On the third hand the designers who look around themselves and say “The world is full of mysterious premises and operating principles and if you want to know where you’re going, maybe it is a good idea to examine how these principles and premises have worked in the past and see if there is a track record that you could follow –given that these premises will get in front of you anyway, no matter what you do.”

Right now I’m looking at design completely different than I did when I was at BMW. And that’s because I’m in a totally new situation: I have my own company, it’s a consultancy firm. We work for a myriad of clients outside of the automotive industry as well, but a couple of things have also happened to me in the meantime, “epiphanies” if you will, which have awaken some dormant thoughts of how real-world design should be happening if we had our collective act together. These thoughts are the ones that I’m trying to somehow understand, codify and realize.

Generally I try to see the world in terms of a multiplicity of solutions that somehow have to be combined. Instead of saying “A or B” I am trying to find how you can get the “A&B –and while you are doing it, you might find a C and then a D you didn’t even know was there”. When you’re inside the industry, quite often there is not a tolerance for that, it’s not too much time for it, people tend to say “A or B, which way?” and since there is not much time and tolerance for thinking; you have to make a hard-core decision on the spot with insufficient research and build everything from that.

The other thing I have am trying to do –– and this I would ask your readers to consider –– is to look at the world of design-creativity as an endless stream with many contributors instead of a one-time phenomenon coming from the pen of some famous-star-designer. The problem with “the star designer” is that everybody else who is in the execution process either does their job 100% right or 100% wrong ––like a machine.

I’m trying to empower the people in my projects; to help them understand they are all active participants in a seamless creative change process. To make everyone be engaged and to somehow actually experience a contributive participation…instead of me the designer saying: “Okay, here’s the design, I’ve drawn it, now you take it and if you screw it up God help you”.

But this “empowerment approach” is not how we generally see design today. We tend to see designers as someone who belongs within an elite group – ‘designers, wow!’ …and all the other poor folks just observe these minor gods at work. It is, as Eric Gill would say, “Inhumane”, and I’m not advocating that at all. But I’m also not saying that everybody can become a designer, just that everyone should be an active contributor.

BB: Actually, to go a little bit further, at what point does fashion interfere with design? Your first example of a designer is a fashionable person, they take what’s existing and they put their stamp on it. How does fashion degrade design?

CB: You’re right on with your observation – I’m just not 100% sure the word “fashion” should be used there. There is an incredibly strong self –delusory process happening, where the norms of “fashion”––or in this case car design––and the aesthetic sense of the particular times we’re surrounded by have become so dominant and terrifying in terms of a “group-think” that nobody wants to leave the safe zone. A group-think, that indeed colors all our thought and changes our opinion until it convinces ua that what we’re doing is “new” when often in reality it is stupid and jejune.

I watched the film today of the new Dodge Dart. The ad’s about “how to make a car that changes the game” or something like that. Sorry it is a nice car, but this car changes the game about as much as the 75th edition of Monopoly. But then what is a “game changer”, really? I keep expecting a generation to come along and show us all what idiots we are and that hasn’t happened.

Shifting gears a bit we asked about the direction of design and this is where the revelatory aspect of the interview occurred based on what we considered a relatively innocuous question regarding how electrification would impact design in the next 25 years. Chris has been doing some thinking about this and gave us an unexpected dissertation on the future of the automobile as we know it.

CB: You asked about electric cars and the premise of “what happens 25 years from now?”. Of course I can only speak as a designer, and consider what I believe are design issues. Probably 25 years from now the critical issue in car design will not be: “electrification yes or no”, but “do the cars drive by themselves or not?”

If you look at the history of cars from a car design point of view, you really can’t tell when one car was a diesel as opposed to gasoline powered, and even the electric vehicles compared to the non-electric vehicles have really no differences visually speaking. Look at the grill on a Tesla; is that for a radiator? It’s splitting hairs to tell whether it was the drive-train that drove this package in this way or other issues.

The reason for this is that physical masses of energy absorption involved in protecting the occupants from crashes are measured in cm of crash zone, and such non powertrain-oriented –but occupant critical– issues give similar types of volumetric relationships to all designers for them to play with.

On the other hand, a car that drives by itself can be radically different than a car that you have to drive. You don’t even need a windshield or headlights. If you’re asking yourselves “how likely is that in 25 years?” I would risk right now to say, “it’s a lot more likely you can buy a car that can drive by itself than electric cars will be the majority of those on the road in 25 years.”

Driving by yourself is a very mundane application of people precious time––applied across million of hours. To be quite honest —and not to belittle the superhuman efforts that have made it a reality– you could convert any vehicle to self driving as long as you can apply devices that take over the steering wheel and the powertrain. There are already lots of sensors on board and room for more.

It used to be thought of as impossible. Google is now out there proving the world wrong, that what couldn’t be done they’re actually doing . . . and with such apparent ease everybody else say’s “I kinda wish we would have done that”. This demonstrates commitment, and they’re obviously going to make self-driving cars a reality. I’m quite certain 25 years is an upper limit for this.

Why all this effort? Because at the end of the day they’ll own the road of the future, which will be this virtual road that all these cars are going to drive on. How about that? We put a whole bunch of tax money into an asphalt highway and it turns out there is an invisible highway that somebody else is building as we speak!

BB: So how will the cars be different? What do you get to do differently with the car that drives itself?

CB: Well basically you can ignore driving – the car is just a carrier for you. You’re not necessarily obligated to be in a front-facing position. An infinite variety of positions will occur in self driving cars, but there are rear-facing seats in vehicles today so there is nothing that says “you absolutely have to have 4 people facing forward”.

BB: So the type seating, vis-à-vis?

CB: It would be quite interesting to see a world where cars have no headlights – quite the energy eaters—and no taillights, and perhaps the exterior of cars will be made of highly reflective materials so that those few vehicles out there driven by humans can pick them up at night. Stuff we know becomes options instead of ‘must-have”, such as headlights are today.

I imagine in 25 years the technology will be mature enough that we could say “at no point does the physical driver have to take over, therefore the entire “transportation thing is a sealed experience”.

But really how possible is that? 25 years from now will take us to 2037 and the current paradigm model of a car is due to expire in around 2040. I suppose you’re going to ask “How do you know that”, right?

Well, there’s a nice magazine article I came across from many years ago, predicting the length of phenomenon. It’s in the New Yorker, July 12, 1999. It’s an article about Richard Gott the 3rd, and it’s an article entitled “How to Predict Everything”. I used the technique to predict the length of the current car paradigm. At that time [this was about year 2000], because my predictive model said the car paradigm changed in the 70s – 80s, I imagined that because according to his theory that says whenever you look at a phenomenon that has a fixed beginning, the highest probability is that you’re in the middle of the lifetime of said phenomenon, that would mean that as of the year 2000 I was at the highest probability to be in the middle of the paradigm we know as cars today. Which means that that phenomenon will peak out around 2030-2040. So 25 years would put you pretty much in the middle of that end phase.

A brief explanation of J. Richard Gott III’s prediction theory is in order. Basically there is no reason to believe we are in anything but the broad middle (within 95% of the total – in other words we can say with 95% certainty they we are not at the beginning or end) of the life-cycle of a product or species. Now the 2.5% on either end of a life-cycle (that outside the broad, 95%, middle) represents 1/40th of the total each (100/2.5=40). So if, say, dogs have been domesticated for 15,000 years you could believe that domesticated dogs would still be around for anywhere from 375 to 585,000 years. It’s an interesting prediction tool, and it can be applied to phenomenon other than life forms. And for things like products the time frames are compressed of course. An excellent analysis of the theory can be found in Timothy Ferris’ article for the New Yorker, ‘How to Predict Everything’. (If you are not familiar with Timothy Ferris, might I suggest his book, “The Coming of Age of the Milky Way”.) And that makes the following so important; what follows our definition of personal transportation, is something the next generation – the first totally wired generation – will view the same we way we view biplanes and steam locomotives, quaint and antiquated. That notion is reinforced by the belief that the next generation’s has a lack of interest in automobiling.

BB: How do intelligent devices (e.g. voice interfaces) impact design?

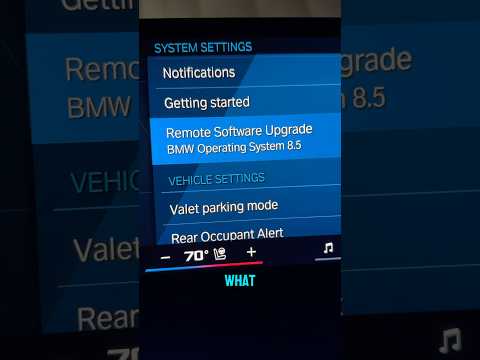

CB: Let’s just stick to car design. Interfaces which are not “throw the switch, push the button” but are much more delicate, such as gesture, voice, command etc. – They are really good except that in the environment of a moving vehicle -where the ambient sound is not under control, a lot of other conditions are not under control- it’s a toughie to get them to always work right.

Voice and gesture control in cars have been pursued for a long time, improvements have been made etc etc. But there still is a long way to go before people feel particularly confident about them. At least to the point where they’re willing to forego a mass of redundant systems.

This is kind of where we’re at right now, we’re at the point where it’s there and you use it sometimes to make a phone call, stuff like that, but other times you’re just as glad that there’s a button to push.

Until now we haven’t got a voice command that holds your cup of coffee so there are still some pieces of hardware to be put in a car, but that can change too. I think in general the question is ‘how much of your driving style will be decided by these devices’ as opposed to these devices that want to conform to your driving style.

I’ll give an example: the aforementioned self-driving cars. There is legislation being discussed right now in America to prohibit telephones in cars – not just for your driving, but in general, because it has been demonstrated they are an addictive medium. And it seems like there is no way to avoid a conflict of attention if a telephone is at all available in the car. Even with hands free and features like that.

Now imagine if, right now, you had the choice between buying the car you drive yourself and NOT having a cell phone in it, and buying a car that drove itself and you can have a cell phone in your car and surf the web and talk and text all you want. Now tell me which one are you going to buy?

We already succumb to the incredible power of our smart devices. To the good and the bad, and that will change radically our priorities in cars.

BB: And then, if that comes true, if this sort or that sort between the two, I would suspect that only a small fraction would choose to drive themselves.

CB: It’s not a bad thing. If you look at the history of the automobile, it’s credited with freedom. To many people it is considered the freedom of destination choice or movement – which is of course true. I would argue it is the freedom to go at your own pace, since horses, bicycles and walkers all let you choose a destination but unfortunately all horses walk at the same speed, etc., unless you are Lance Armstrong, only cars let you truly pull away from the pack. But more importantly, the automotive radically changes peoples’ ideas of self-empowerment.

Before the automobile came along, anyone of means was served by a driver. If you had a horse carriage and if you had any sort of money you had a driver who drove it. What happened to the automobile? Certainly the car driver has all kinds of cool gizmos and the feedback of driving is much more direct and maybe more satisfying than you get from a horse.

The actual act of commanding the horse while it is pulling the wagon is perhaps less direct and in a certain sense less pleasurable than the feeling you get from a steering wheel or a gas pedal. In that phase where the automobiles moved from a rich man’s toy to the every man’s mobility, the rich men also discovered they wanted to do this driving work, too. And that redefined your idea of ‘what is it I myself do as a successful person.

Now we’re going to another empowerment phase – with the smart devices. And what we are learning with that empowerment phase – a critical one I feel – is that for the first time people are becoming truly universally multi-taskers. Today almost 85% of people who watch TV are working on their phones, email, Facebook, etc. This is a “social-network-gatherer-weaver” mode we are practicing…and culturally very much our collective “female” side.

In the past you could literally have a book in the lap and watch the TV before you, but now you can command 3 or 4 different things while watching TV. As we are becoming true multi-taskers the male dominated image of how the world works – a single-minded, singular-purpose oriented world––is being impacted by this release of our feminine side. And as such our preferences – “I’d rather have some kind of personal activity device than a set of wheels” –leaves many “car-guys” a culture trapped in the vehicle they still need to “dominate”. If evidence demonstrates that’s truly what’s happening, it’s a fundamental shift in our own priorities – and a good one, too.

And that brings us to the fate of a car company’s future that has hung it’s hat on the ‘Ultimate Driving Machine’, where does that fit if you don’t drive a car anymore. Bear in mind that a company as powerful in its industry as Kodak is now in bankruptcy, a victim of the digital age (and Kodak created the first digital camera!). They were engrossed in the medium and not the function the product was performing.

BB: Now the fun thing is that at this point, the companies that have built the reputation on cars that celebrate the act of driving have to be thinking just a bit.

CB: It’s not for nothing that BMW switched their campaign from ‘Freude am Fahren’…to ‘Freude.’

We have mentioned before that BMW has said that they build premium personal mobility . . .