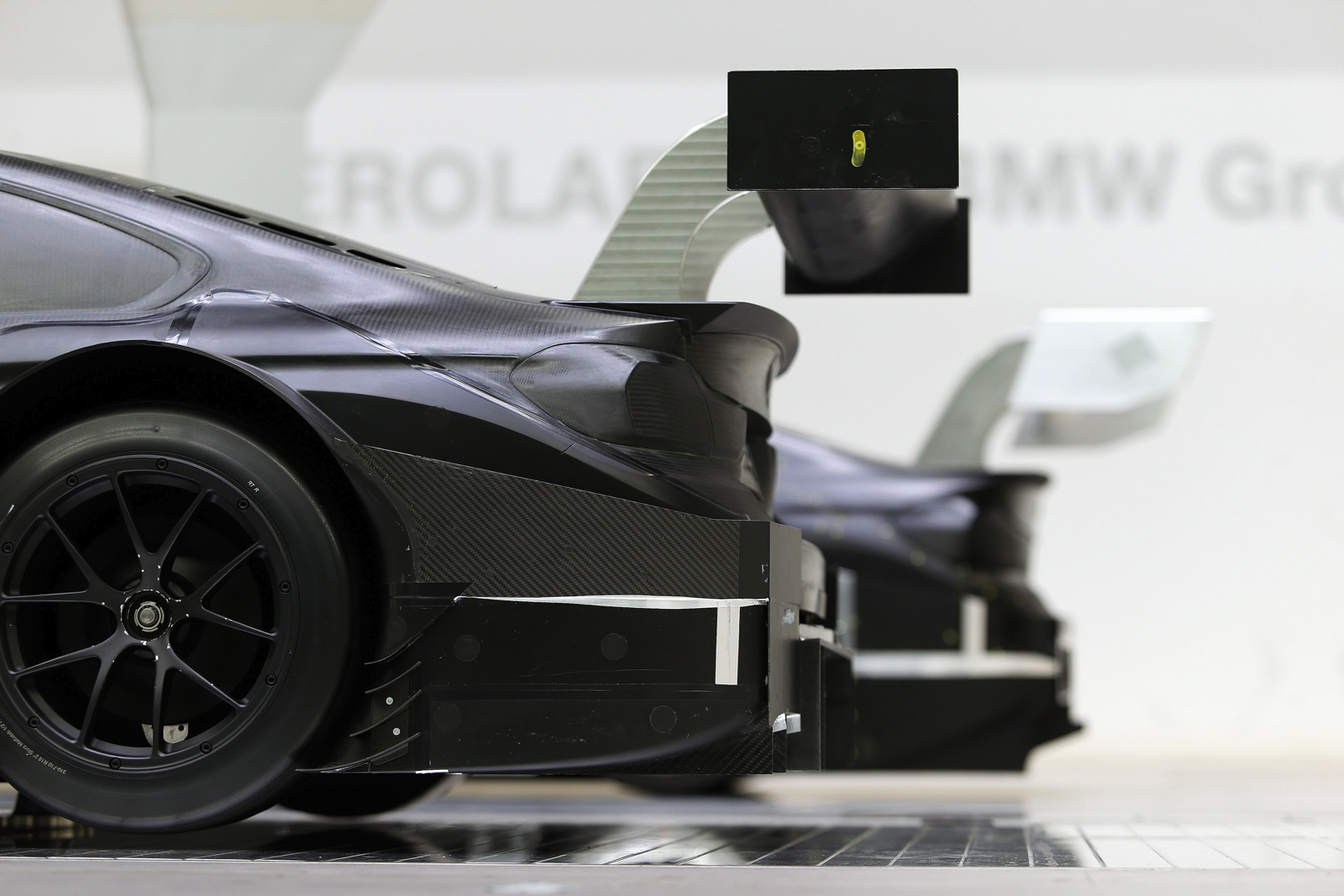

The adjustment of the aerodynamics to the requirements of the new DTM technical regulations played a decisive role in development of the 2017 BMW M4 DTM. The work carried out on the BMW M4 DTM in the wind tunnel prior to the start of the 2017 DTM season has changed considerably. Previously, the aerodynamics specialists had more time to carry out detailed work to ensure optimum aero efficiency when developing a new car. Now, a day in the state-of-the-art BMW Group Aero Lab is more akin to a day at the racetrack.

50 times 15: this was the formula used by the aerodynamics experts at BMW Motorsport when developing the new BMW M4 DTM ahead of the 2017 season. 50 days in the wind tunnel were permitted, with a maximum 15 hours per day. Not a minute more. In order to keep cost of developing the new DTM cars down, the German Motorsport Association (DMSB) worked with the manufacturers represented in the series to limit development time in wind tunnels. To take full advantage of the limited time allowed, the airflow specialists scrutinized their own processes and methods – with enormous success.

Race against the clock.

In modern motorsport, maximum efficiency is not only a key factor at race weekends, but also in the development process. Every minute counts. The planning of a wind tunnel session was completely adapted to the new regime for the BMW M4 DTM, and is similar to a test day at a racetrack. The engineers first define the initial configuration, then they set about creating a precise schedule for the subsequent tests. The focus was set primarily on the structure of the model car being tested in the wind tunnel. Compared with the development of the 2014 BMW M4 DTM, it is assembled in a more modular way to allow faster modification of the aerodynamic details. For example: the tests use a bonnet comprised of eight individual components that can be exchanged separately.

Precision is key.

Depending on the complexity of the parts to be switched, the aerodynamicists at BMW were able to test, on average, three car configurations per hour. The model was prepared, mounted on a hexapod and precisely positioned with maximum tolerances of a hundredth of a millimetre to allow the simulation of different driving situations, such as fast corners, tight hairpins and straights. While a 60 percent scale model of the BMW M4 DTM was still under construction, work was already underway analysing the data gathered. Ultimately, no further test time could be wasted on a configuration that had not previously achieved the desired result.

All these steps followed each other faster than before, but with no less accuracy. An old motor racing adage still rings true: every tenth of a millimetre counts in the wind tunnel. These can then be converted into tenths of a second out on the racetrack.