Nico DeMattia covered the story of the BMW Z1’s doors in a recent article on BMWBLOG. Reading that reminded me that the newly formed BMW Technik, in 1985, was the origin of the Z1. As its first fruit, the Z1 was a showcase for the capabilities of the group. The Z1 explored special production techniques, suspension techniques, and an unusual ingress/egress technique with its special doors.

As neat as the doors are, I’m reminded of the old joke about selling toothbrushes that includes a bit about, “You need a gimmick!” The doors are a way of capturing attention (or a magician’s misdirection from something more significant). While people focused on the Z1’s doors, BMW Technik explored a production technique that would allow them to build and update lightweight low volume cars.

There’s a slim, but expensive, volume on a bookshelf in the den titled, “Quick Die Changes”. The state of the art for changing dies on an assembly line in the 1980s was glacial. Dies are used to stamp body panels. They sit in a hydraulic press with a piece of flat steel sheet slipped between the die halves. The press closes (presses) the die halves together and imparts a three dimensional shape to the piece of sheet steel.

It is the speed of die changes that determines whether or not ‘custom pressing’ of small lots make sense. Having to shut a production line down for hours to change dies mitigated against low volume specialty cars, especially for a company where volume production is necessary to cover costs. (Now, die changes can be completed in minutes – a trip to the Leipzig plant included watching a Schuler press spit out panels for one version of 1 series only to return to the press moments later and see an entirely different version of 1 series panels being stamped.)

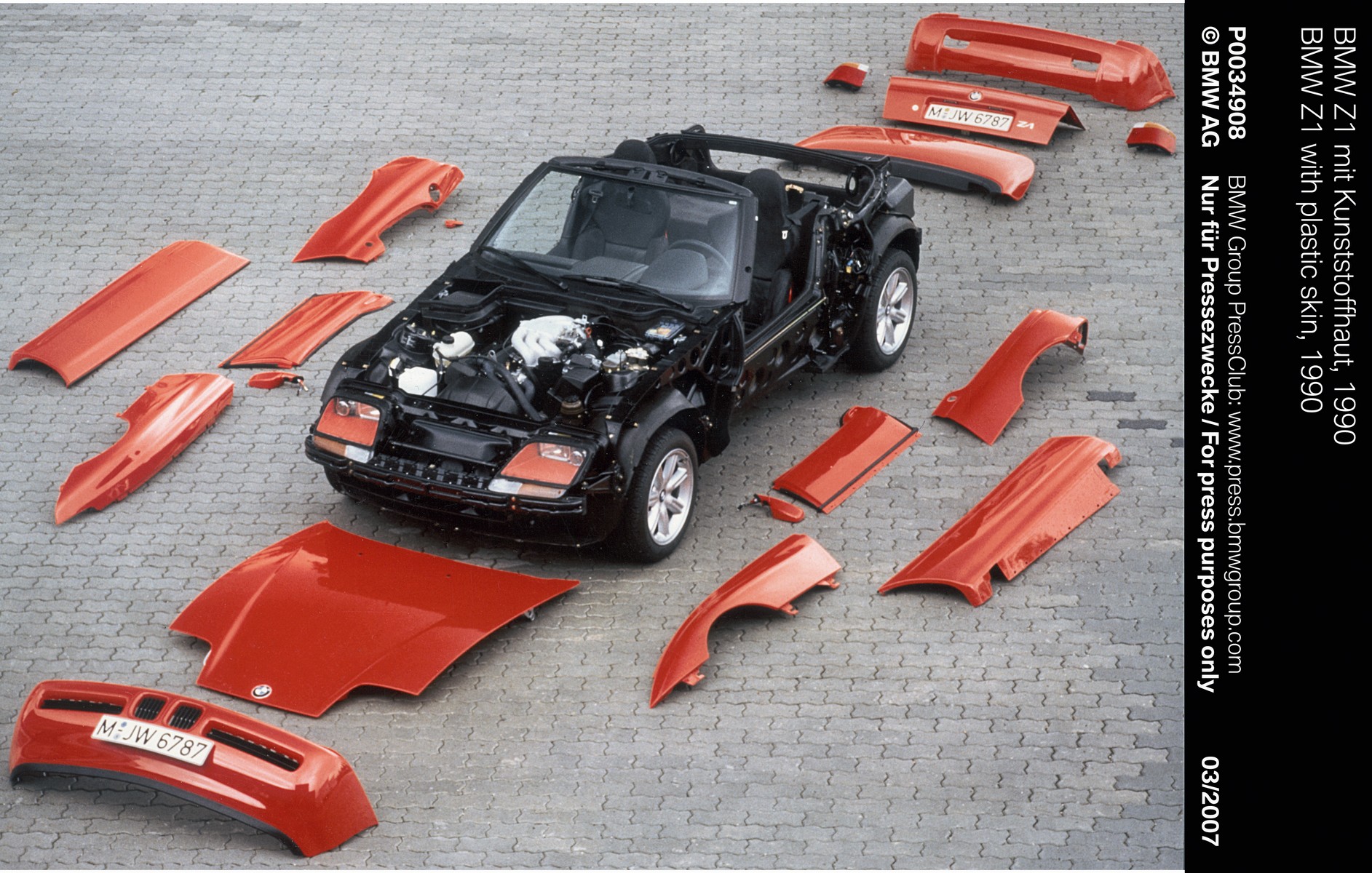

However, in the late 1980s, knowing that styling updates have to be done, and weight is the enemy of sports cars, the exploration of different means of ‘skinning’ a low volume vehicle made some sense. General Motors got there first with the Fiero. It employed a steel skeleton and plastic body panels. The Z1 was similar but BMW Technik used a steel skeleton with a special composite floor developed by Messerschmitt and body panels made from GE’s Xenoy (a polyester and polycarbonate plastic with some interesting properties – in particular durability).

In full production, set up in a portion of the massive Munich facility, about 16 Z1s could be made each day. Enough to satisfy demand (and not be a drain on the company).

At the end of the day the Z1 gave BMW Technik a feather in its cap, it explored several novel and useful features that could be employed in the future. And the most important piece of the Z1, from a corporate perspective, was the Z-axle employed at the rear of the car. That multi-link rear suspension setup would go on to replace the rear trailing arms in use on BMW models.

BMW Technik would go on to become BMW Forschung und Technik and it would play an ever more important role in how BMW cars would look, drive, and – most importantly – be built.