At a vibrant event at New York’s Guggenheim Museum on June 28th, BMW announced Julie Mehretu as the 20th Art Car artist. The vehicle chosen as the next Art Car canvas is the BMW M Hybrid V8 race car, which will race the famed Le Mans 24 Hours event in 2024. The canvas for Mehretu’s Art Car made a splash the weekend before the Guggenheim unveiling by earning its maiden victory in the IMSA GTP-class at Watkin’s Glen in upstate New York.

Julie Mehretu: An Artworld Superstar

Julie Mehretu was born in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, in 1970, and along with her family moved to the USA at the age of seven. She received her B.A. from Kalamazoo College, Michigan, graduated from The Rhode Island School of Design with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1997, and spent a year studying at Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar Senegal. Known primarily for her layered, narrative, large-scale abstract paintings, Mehretu’s work incorporates themes as diverse yet interrelated as politics, literature, and music. Her paintings have an unmistakable dynamic vibrancy, with her latest work blending images from media depicting conflict, societal injustice, and social unrest. She has maintained a studio in New York City since 1999.

Mehretu has received numerous awards for her work, including a MacArthur Award and the US Department of State Medal of Arts Award, and in 2021 she became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Design.

Mehretu’s BMW Canvas

Returning to prototype racing for the first time since 1999, when the BMW V12 LMR won the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the BMW M Hybrid V8 is powered by a 4.0-liter, eight-cylinder turbo engine coupled with a supplementary electric motor. (The P66/3 combustion engine is based on the unit used in the BMW M4 DTM in 2017-2018.) This hybrid drive system has a regulated output of approximately 640-hp and makes approximately 650-Nm of torque, good for a maximum speed of up to 345 kph/215 mph, depending on track layout. BMW’s chassis partner for the car is legendary Italian race car specialist Dallara. The Italian designers are among the most successful manufacturers of race cars in the world.

A Unanimous Nomination

In 2018, an international jury, composed of artworld heavyweights from the museum and gallery worlds, met to consider the next artist to be selected for the BMW Art Car program. Julie Mehretu was their unanimous choice.

“Julie Mehretu is the perfect artist for this early 21st century,” said Madeleine Grynsztejn, Pritzker Director, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. “To merge her work with the shape and form of a speeding vehicle is really an alignment of perfection. For years, Julie has painted speed and for a long time worked very successfully at scale. This means to me that she will be able to create a form that you can see from a distance because with many of her large commissions, you need to back up to really enjoy them. She has an understanding of space and speed that is a perfect partner to the BMW Art Car.”

Other Jurors were equally effusive in their praise. Okwui Enwezor (1963 – 2019), former Director, Haus der Kunst, Munich: “Julie Mehretu’s work incapsulates different questions of movement. She expresses dynamism within a form. It is a very clear and sound understanding of how the object acts in space. And I think this really makes it a very exciting proposition to have an artist of her caliber who has the long-standing experience to take on this project.”

BMW & The Art World

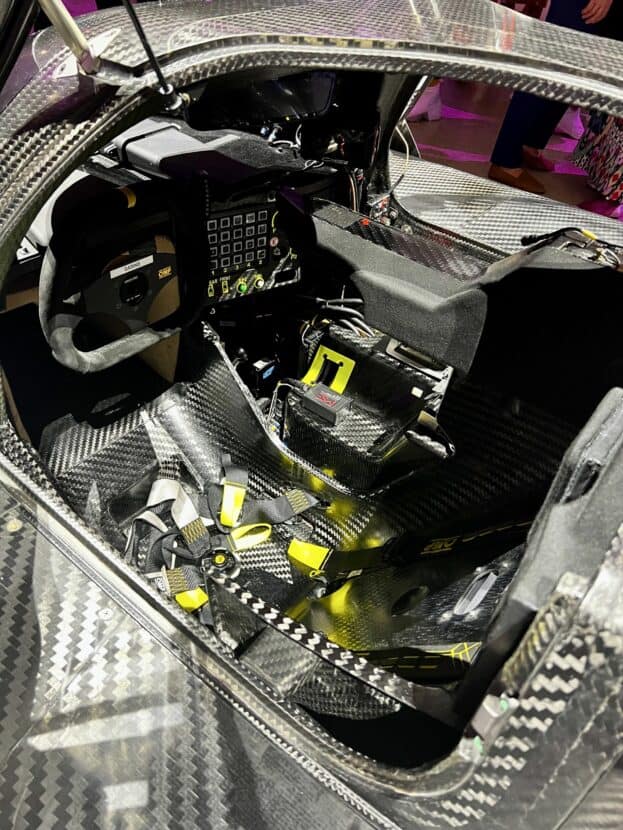

At its unveiling, the M Hybrid V8 sat like an otherworldly movie prop in the lobby of the Guggenheim’s alabaster main hall, the car’s naked carbon fiber body hinting at design possibilities to come. Previous Art Car artist Jeff Koons snapped pictures with his mobile phone, while various dignitaries and enthusiastic supporters from the art and automobile worlds took in the stunning architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic building. Club music pulsed and an innovative multimedia display projected names of previous Art Car artists and car images on the swirling interior balconies of the building. BMW also exhibited models of each of the previous Art Cars, in display cases fit for a museum (certainly appropriate in this instance.)

BMW’s involvement with the Guggenheim goes back to 1986, when they sponsored “The Art of the Motorcycle” exhibition, an event with caused quite a stir in both the art and motorcycle/automobile communities for its then-novel juxtaposition of two seemingly disparate worlds. The event proved prescient, though, as it foreshadowed how the art and corporate design worlds would blend seamlessly in many different venues and occasions over the next few years. It also deepened BMW’s significant involvement and support of visual arts programs worldwide.

The BMW Guggenheim Lab

In 2011 through 2014, BMW partnered with the Guggenheim for the innovative “BMW Guggenheim Lab,” which travelled to major cities (New York, Berlin, and Mumbai) aiming to inspire an ongoing conversation about important urban challenges around the world. The company has also been a supporter of the Art Basel series of art fairs (particularly in Miami) for many years, an event they’ve used to introduce numerous new design directions and stylistic themes.

Why is BMW so visibly committed to supporting the arts? According to Ilka Horstmeier, Member of the Board of Management of BMW AG, People and Real Estate, Labour Relations Director, it’s been BMW’s philosophy to do so for over fifty years. “It all started with Gerhard Richter (referencing the artist from whom BMW commissioned three major paintings in 1972 for its Munich headquarters). We wanted to give our people an inspiring work environment, and supporting artwork was an integral part of that. [Art] is deeply rooted in BMW’s genes.”

Moreover, she’s clear about the value to BMW’s brand from its support of the arts. “We’re not just here for altruistic reasons. People get emotionally attached to these cars. That can only be good for BMW’s business.”

BMW Art Cars: Literal “Performance Art”

The history of BMW’s Art Car program is as unexpected as it is delightful. In 1975, Frenchman Hervé Poulain, a young auctioneer and racing driver, hatched a plan to combine his two life passions into one. He approached Jochen Neerpasch, founder of BMW Motorsport, about providing him with a BMW 3.0 CSL to run in the 1975 Le Mans 24-Hour race, and approached his friend, American artist Alexander Calder, about creating a memorable design for the car.

As reported by French auction house Artcurial, Poulain purchased a model of a 3.0 CSL from a toy shop and set off to meet Calder in Saché, France, where he was staying. Calder bought into the plan. Over lunch, Calder wrote out in longhand to Neerspasch his commitment to participate: “OK to paint the car of Poulain and his colts, regards to everyone.” The French word “poulaine” means “colt” in English.

Recognizing the unique value they’d created, BMW insured the car for DM 1 million (~US$430,000), and Poulain (along with co-drivers Sam Posey and Jean Guichet) ran a competitive race until the sixth hour, when the car was retired with a broken driveshaft. Though an unfortunate result, the car was a big hit with both fans and BMW itself. The Art Car program was born.

In a wonderful postscript to that effort, when the Andy Warhol M1 Art Car raced at Le Mans in 1979 and finished sixth, one of the three-driver team was, fittingly, none other than Hervé Poulain himself, his efforts justifiably rewarded with a place in both art and racing history. “I love this car. It’s better than any work of art,” said Warhol about his design.

Over subsequent years, BMW engaged additional art world luminaries, such as Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, David Hockney, Jeff Koons, Ken Done, Sandro Chia, Coa Fei, and others, to express their artistic visions using the mechanical palate of various BMW cars. Until 1986, all the Art Cars were racing cars that participated in race events. With Robert Rauschenberg’s 635 CSi in 1986, BMW began to work production models into the Art Car mix. (And in the case of Ólafur Elíasson, something different entirely).

In all, BMW has partnered with nineteen artists since 1975 to create these unique rolling artworks, the most recent being John Baldessari’s M6 GTLM in 2016, which raced in the IMSA series in the US. (Baldessari notably said of his car, “[it’s] the fastest artwork I’ve ever created.”)

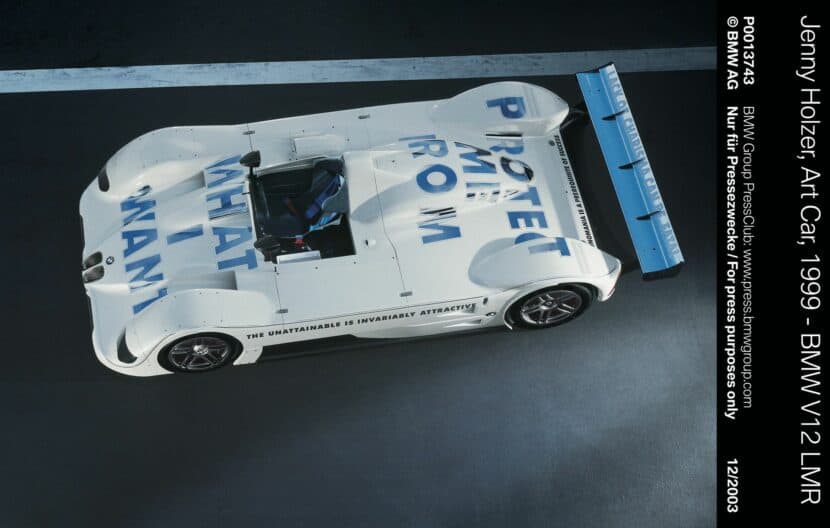

My Favorite? Jenny Holzer’s V12 LMR

This writer’s favorite Art Car has to be Jenny Holzer’s V12 LMR, which raced at Le Mans during the 1999 campaign. The white racing car was painted with phrases from Holzer’s “Truisms and Survival Series,” such as “Protect Me From What I Want” and “Lack of Charisma Can Be Fatal,” in vibrant chromium and phosphorescent paint. Holzer, whose father was a car dealer, brought her trenchant criticisms of Western society to the vibrant and iconic racing event in a subtly provocative manner. While Holzer’s Art Car didn’t finish the race, one of its sister cars claimed the overall victory.

Perhaps surprisingly, artists aren’t directly compensated or actively recruited by BMW to participate in the Art Car program (though they are provided significant materials), but this also provides each artist with total creative freedom; once selected for the program, BMW has steadfastly taken a “hands off” approach to what each artist creates. In a 2020 interview in British GQ, former BMW Board Director Ian Robertson said, “Artists have to want to do this, they come to us. We don’t pay them, either. The lure is that they become part of history,” added Robertson. “The moment you say, ‘You don’t have total creative freedom’, then what’s the point?”

All in all, artists from over nine countries (and five continents) have been represented in the Art Car program. After being raced or completed, the Art Cars are kept and maintained by BMW at the BMW Museum in Munich, and periodically turn up at automobile and art events around the world, providing both art- and BMW-aficionados the rare opportunity to see these unique creations.

You can find a full list of the existing nineteen Art Cars HERE.

What’s Next for BMW Art Car #20

Julie Mehretu has already begun working on her final design for the car, first on a 1/5-scale model and ultimately on a full-sized version later this year.

With weight so important to racing machines, the specific materials for the car’s finish are a consideration for the artist as she works with the BMW team. Said Timo Resch, Vice President Customer, Brand, Sales at BMW M GmbH, “She envisions her final artwork to be very lightweight,” explaining that the team is working through whether to use a wrap of some sort, airbrushed paint, or some combination of the two materials. “She absolutely doesn’t want to compromise the car’s performance.”

He paused and chuckled a bit. “Though if she comes up with some aerodynamic device that improves the car, we’re all for it.”

At the Guggenheim, after being introduced by Thomas Girst, Global Head of Cultural Engagement at the BMW Group, Mehretu spoke about how pleased and honored she was to be included in such significant artistic company, and her thrill at tackling the design challenge.

“This is a moment to push the [design] of the vehicle to be more than the car can otherwise be. That blur of a racecar going by is one of the first things that struck me when I saw this car on the racetrack,” referencing her visit to Daytona earlier in the year to see the car perform its initial on-track tests. “That moment of a car speeding by, the uncertainty of it, is interesting for me to investigate. And a big part of art is play,” she added. “That uncertainty, of a racecar at speed on the edge, is something I want to explore in creating something like this.”

To Be Unveiled Before June 2024

With the official announcement of both the artist and platform complete, the question of when the public will see the completed car was on everyone’s mind. At a breakfast for the press the morning after the evening Guggenheim event, a questioner asked Ilka Horstmeier when we might see Mehretu’s finished Art Car. She paused before speaking, looking a bit mischievous. “Timo, how many days until Le Mans?”, she asked Resch, who was sitting at a nearby table. “364 days,” he answered. She smiled before answering the questioner. “Well, certainly no more than 364 days.”