The story of the original BMW ‘Neue Klasse’ is not just the story of a series of cars based on the BMW 1500, but a story of survival, and subsequent revival, in the face of certain corporate death. BMW was in crisis in 1958. It was a full decade since German currency reform occurred, which split the country between east and west. For the west, currency reform meant a financial renaissance – the “Wirtschaftwunder”. The Suez crisis of 1956, which had crippled middle eastern oil imports into Europe, and strengthened the market for “bubble cars”, was now in the rear view mirror.

Given a healthy economy and ready access to fuel, Germans lost their taste for motorcycles and ‘microcars’. They looked forward to family-sized vehicles that would satisfy the emerging affluent middle class. Subsequently, a number of “bubble car” manufacturers went out of business in 1958, Brütsch, Fuldamobil, Heinkel, Kleinschnittger, Maico, and Zundapp among others. BMW itself was on the cusp of failure.

Survival and Revival

BMW had just barely survived World War II and as it emerged from the doldrums, it was decided that an emphasis would be placed on expensive – low volume – cars, given the state of production facilities and available skilled workforce. The Baroque Angels were the result and were followed by a number of like models, the 503, 504, and a handful of 507s that would reuse tooling and parts for the large cars. However, BMW became reliant on its “bubble cars,” the 250, 300, and the 600, for the bulk of its sales.

Dr. Heinrich Richter-Brohm, BMW’s CEO, laid the groundwork for BMW to build a mid-size model. It was hoped that this could bring a new class of customers to the marque. BMW had studied consumer desires and knew they needed a mid-sized offering that would appeal to the emerging middle class. The problem, as is often the case, is how to finance the development of a new car. The design, engineering, and production resources required to bring a new model to market can’t be done on the cheap.

Dr. Heinrich Richter-Brohm and the Mid-Size Vision

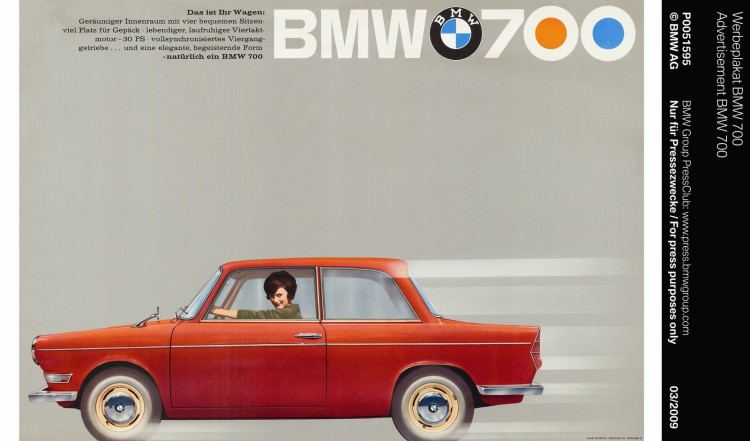

Without a mid-size model on the market, a more desirable small car was desperately needed to keep cash flow going. The Michelotti-designed 700 – a “poor man’s Porsche” – was purposefully designed to reuse as much as possible from the 600. The 700 was presented to the board in the middle of 1958. It had been created for BMW by Wolfgang Denzel, the Austrian BMW importer. The 700 foreshadowed the eventual ‘Neue Klasse’ in its monocoque chassis and semi-trailing arm rear suspension. It managed to sell well enough to keep the company afloat.

BMW had started addressing the design of a new mid-size vehicle in 1953. BMW examined different proposals for engines as well as a number of designs for the car itself. Many of the drawings for the car aped the then-current styles – basically ¾ sized American sedans, replete with styling gimmicks that were not unlike contemporary mid-sized mass-market German cars.

Early Prototypes and Challenges

One approach to the new mid-size car led to the design of the M530 engine of 1.6-liter displacement, based on one bank of the existing V8. This was the powerplant that went into the handsome 530 prototype. But without funding, the 530 died on the vine. It was a shame the 530 did not go into production; it was a timelessly styled beauty. The BMW Dimensions Book #2, The History of Engines – Engines That Made History, 1945 – 2000 has a number of photographs of the 530 prototype on pages 166 and 170. (It is unfortunate that searches on the internet do not return images of this car.)

Rejecting the M530 engine, BMW then looked at the M109 four-cylinder (0.9 liter) as they continued to explore a mid-sized offering. The M109, however, was limited by its bore spacing, so an engine with larger bore spacing, the M115, was conceived. Attempts to create an aluminum alloy block did not deliver expected results, so a cast iron block was selected with an aluminum cylinder head and single overhead camshaft. BMW would designate this as the M10 engine in 1963, which applied to any inline four-cylinder with 100 mm bore spacing. It is the M10 that would go into the ‘Neue Klasse’ cars.

The December 1959 Crisis

Unfortunately, the funds available to BMW, even with the profits from the 700, weren’t enough to cover the investment needed to build the mid-sized car. In December 1959, BMW was on the block – destined to be absorbed by Daimler-Benz. A board member had arranged a ‘fire sale’ price for BMW, and it would have been absorbed whole into Daimler-Benz. Tenacious opponents to the sale, along with balance sheet improprieties, punctured the plans to sell the company; while in the background, work was already underway to deliver control of the company to a sympathetic savior, Herbert Quandt.

One potential source of funds was the sale of BMW’s aviation factory. BMW had created a subsidiary to manufacture aircraft engines at its Allach facility in 1954. By 1958 it was making license-built AVCO – Lycoming piston engines and later obtained a license to build the GE J79 jet engines for the Luftwaffe’s F-104 Starfighter program. The funds needed to support these activities were directly competing with the funding required for the ‘Neue Klasse.’

The Allach plant was a desirable property, but BMW was looking at an all-or-nothing sale of Allach and the Milbertshofen production facility, with the hope that the buyer would continue to implement BMW’s production plans. In the end, a fifty percent stake in the Allach facility was sold to MAN, and the Quandts arranged additional financing to allow BMW to move forward with the “Neue Klasse.”

The BMW 1500: A Game-Changer

Finally, work on the new BMW mid-size offering could proceed. The previously mentioned M115 engine would become the heart of the BMW 1500 shown at the Frankfurt International Auto Show in 1961. It produced more power than similar-sized contemporary engines. The 1500 also had fully independent suspension, front wheel disc brakes, and a clean, conservative style. The design of the 1500 was under the direction of Hofmeister’s Bodywork Development Group – with Michelotti’s input since BMW did not have a separate design studio at the time.

Key Design Features of the BMW 1500

The BMW 1500 was a hit. A clean car with taut surfaces, it appealed directly to the times. Its three-box design with capacious storage for luggage and more than adequate room for four or five passengers was what the emerging German middle class desired. Some styling cues that would become BMW hallmarks were also seen on the 1500. A horizontal front grille with two round headlights interrupted in the middle by BMW’s iconic twin kidney grilles. A swage, or ‘sicke,’ line that ran horizontally below the greenhouse emphasized the car’s length (while its real purpose was to add strength to the sheet metal), and then there was the Hofmeister kink. Its stacked vertical taillights further added to its stylishly conservative look, just what the good German burghers were looking for.

Further enhancing the 1500’s appeal was its power and ride quality provided by the all-independent suspension. Jeremy Walton, in his book, BMW ULTIMATE DRIVERS VOL I: 1937-1982, detailed the driving experience of the 1500. He noted the four full turns lock to lock of the unassisted worm & roller steering gear, and that the car rode on tall skinny bias ply tires, which could be a bit of a handful in the wet. But in the dry, it was a vice-free, comfortable driving machine with more power than its peers.

BMW now had to squeeze production into the crowded Milbertshofen facility while training its workers and creating, marketing, distribution, and after-sales support. There were bumps along the road, particularly quality issues – both in design and execution – of the early examples. But the pieces were finally in place to shine a way forward for BMW.

The Impact of the Neue Klasse

The ‘Neue Klasse’ propelled BMW from a moribund company to one of great vigor. The ‘Neue Klasse’ rejuvenated BMW’s production, marketing, distribution, and sales. It was the right product at the right time. BMW would adroitly use the ‘Neue Klasse’ to position themselves for the booming economic conditions to come.